Do I Have to Draw You a Picture?

Exhibition at The Heong Gallery, Downing College, Cambridge

Review by Robert Good

Exhibition at The Heong Gallery, Downing College, Cambridge

Review by Robert Good

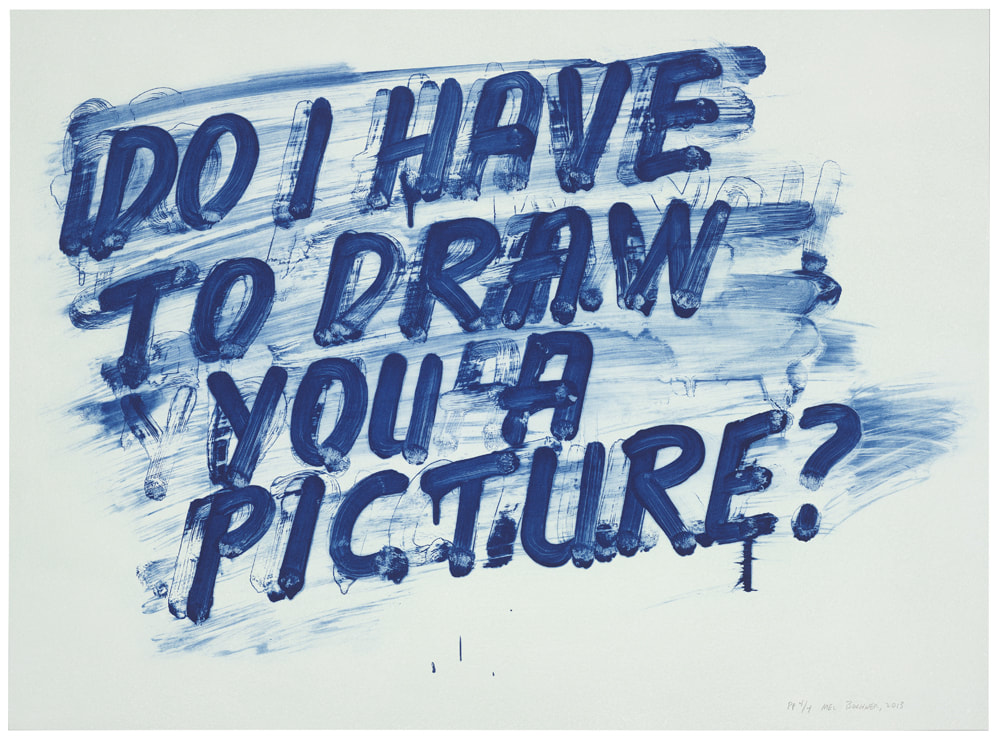

Do I Have to Draw You a Picture? Mel Bochner

Do I Have to Draw You a Picture?, asks Mel Bochner in a brushy blue script that provides the title work for the current survey of text-based art at the Heong Gallery in Cambridge. Is he being ironic? Iconic? Laconic? Who knows.

No, seriously, who knows? Who can say what a particular text means, or what the author of any piece of writing intends it to mean? Are they even the same thing? Such core questions are the building blocks of any attempt to communicate successfully and they have led some great minds - Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Noam Chomsky - to grapple with ideas of language, truth and meaning. At times this can seem like so much philosophical mud wrestling, where even the basic concepts refuse to be pinned down and submit. We are faced with the unsettling conclusion that perhaps words can only ever be approximations, slipping anchor, so to speak, on the first high tide.

The artists assembled by curator Dr Elisa Schaar for this exhibition explore and exploit these slippages and challenge the assumed continuum between communicator and receiver in a pleasingly wide range of treatments. First impressions are always important, and the massive SHE/HE/HER lettering of Kay Rosen's She/Man greets the visitor in a bold, red, vertical array. The scale of the work demands engagement - Rosen is communicating all right - but what she is saying resists a straightforwardly reductive analysis. I notice the backbone 'HE HE HE' makes for a wittily constructed comic-book laugh as well as being a play on the centrality of masculinity, or so I assume. It is tempting at this point in any gallery visit to dip into the catalogue notes for help and advice, for some sort of explanation - am I right? Conceptual art exhibitions in particular can sometimes feel like a series of cryptic clues to be solved.

No, seriously, who knows? Who can say what a particular text means, or what the author of any piece of writing intends it to mean? Are they even the same thing? Such core questions are the building blocks of any attempt to communicate successfully and they have led some great minds - Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Noam Chomsky - to grapple with ideas of language, truth and meaning. At times this can seem like so much philosophical mud wrestling, where even the basic concepts refuse to be pinned down and submit. We are faced with the unsettling conclusion that perhaps words can only ever be approximations, slipping anchor, so to speak, on the first high tide.

The artists assembled by curator Dr Elisa Schaar for this exhibition explore and exploit these slippages and challenge the assumed continuum between communicator and receiver in a pleasingly wide range of treatments. First impressions are always important, and the massive SHE/HE/HER lettering of Kay Rosen's She/Man greets the visitor in a bold, red, vertical array. The scale of the work demands engagement - Rosen is communicating all right - but what she is saying resists a straightforwardly reductive analysis. I notice the backbone 'HE HE HE' makes for a wittily constructed comic-book laugh as well as being a play on the centrality of masculinity, or so I assume. It is tempting at this point in any gallery visit to dip into the catalogue notes for help and advice, for some sort of explanation - am I right? Conceptual art exhibitions in particular can sometimes feel like a series of cryptic clues to be solved.

She/Man Kay Rosen

Of course, art is not simply a puzzle to be solved and there is no necessary meaning that has to be found. And this is what makes art so rich, and text-based art doubly rich. First the words themselves provide linguistic content. Louise Bourgeois spins narratives. Jenny Holzer bombards with slogans. Andrew Herman emits a scream. Partial, obscured, ambiguous: all are simultaneously alluring and treacherous. And then there is their artistic treatment, the delivery mechanism, that may work at a tangent to the words themselves. So we see neon, dot matrix, screen prints, handwriting and more deployed to deepen the resonance of the works and to reference the wider physical world.

But there is a third layer of text in this exhibition, beyond both the 'art' wrapper and the 'text' wrapper. In the corner of several works that are on loan from The British Museum, under the glass and neatly impressed on the mount board, are small inscriptions tagging the donors who made the purchases possible. Named individuals and companies mark out their territory and interpose themselves between artist and viewer to ensure that they and their benefactions will not be forgotten. These acts of institutional graffiti intrude upon the artworks, yet in a strange way they are acts of creativity too: the urge to self-expression. "I was here". Or perhaps "Remember me"?

This exhibition is in many ways an introductory primer to the world of art and text. It acts as a historical survey by including sample works from many heavyweights of the Golden Age of 1960s conceptual art - John Baldessari, Ed Ruscha, Joseph Kosuth - and we are fortunate to see such artists represented in Cambridge. There are more recent artists, too, and not all are dealing with the difficulties of language. In this exhibition Bob and Roberta Smith and Wolfgang Tillmans notably attempt to hold back the current political tide with more unambiguously assertive interventions.

Looking ahead, in this age of alternative facts and truth-is-not-truth post-truth, it is not just world leaders who appear more like circus acrobats or improbable contortionists in their treatment of language. Across the board, language is being subjected to new pressures and new forces. From the mechanisation of language through AI, Tweetbots and Google Translate to the repurposing of language via echo chambers, social media trolls and the migration of text and knowledge from books to the internet: all these appropriations, remixes and hybrid forms generate new texts and new substrates that are ripe for exploration and examination. Material, perhaps, for a sequel to this exhibition?

Wolfgang Tillmans reminds us that "no man is an island", yet ultimately we are all at sea. Words provide us with a semaphore with which to wave to each other, but words are never enough. In a Venn diagram of art and text, art is not a subset of text. There is an intersection but also an irreducible remainder. Art can take you beyond words, into that boundless ocean of unwritten thoughts, feelings, half-formed ideas, dreams and in-between states of being. Art begins where words run dry.

Do I Have to Draw You a Picture?, asks Mel Bochner. I think the answer is: yes please, Mel, you do.

But there is a third layer of text in this exhibition, beyond both the 'art' wrapper and the 'text' wrapper. In the corner of several works that are on loan from The British Museum, under the glass and neatly impressed on the mount board, are small inscriptions tagging the donors who made the purchases possible. Named individuals and companies mark out their territory and interpose themselves between artist and viewer to ensure that they and their benefactions will not be forgotten. These acts of institutional graffiti intrude upon the artworks, yet in a strange way they are acts of creativity too: the urge to self-expression. "I was here". Or perhaps "Remember me"?

This exhibition is in many ways an introductory primer to the world of art and text. It acts as a historical survey by including sample works from many heavyweights of the Golden Age of 1960s conceptual art - John Baldessari, Ed Ruscha, Joseph Kosuth - and we are fortunate to see such artists represented in Cambridge. There are more recent artists, too, and not all are dealing with the difficulties of language. In this exhibition Bob and Roberta Smith and Wolfgang Tillmans notably attempt to hold back the current political tide with more unambiguously assertive interventions.

Looking ahead, in this age of alternative facts and truth-is-not-truth post-truth, it is not just world leaders who appear more like circus acrobats or improbable contortionists in their treatment of language. Across the board, language is being subjected to new pressures and new forces. From the mechanisation of language through AI, Tweetbots and Google Translate to the repurposing of language via echo chambers, social media trolls and the migration of text and knowledge from books to the internet: all these appropriations, remixes and hybrid forms generate new texts and new substrates that are ripe for exploration and examination. Material, perhaps, for a sequel to this exhibition?

Wolfgang Tillmans reminds us that "no man is an island", yet ultimately we are all at sea. Words provide us with a semaphore with which to wave to each other, but words are never enough. In a Venn diagram of art and text, art is not a subset of text. There is an intersection but also an irreducible remainder. Art can take you beyond words, into that boundless ocean of unwritten thoughts, feelings, half-formed ideas, dreams and in-between states of being. Art begins where words run dry.

Do I Have to Draw You a Picture?, asks Mel Bochner. I think the answer is: yes please, Mel, you do.

Do I Have to Draw You a Picture?

16 June-7 October 2018

The Heong Gallery, Downing College, Cambridge, CB2 1DQ

Admission Free

Opening Hours: Wednesday-Sunday 12-5

www.heonggallery.com

Mel Bochner

Do I Have to Draw You a Picture, 2013

Etching with aquatint printed in blue on white wove paper, 56.5 × 77 cm.

© Mel Bochner. Collection: The British Museum.

Kay Rosen

She-Man, 1996 – 2018

Sign paint on wall, dimensions variable.

© Kay Rosen. Courtesy the artist and Philipp Pflug Contemporary.

16 June-7 October 2018

The Heong Gallery, Downing College, Cambridge, CB2 1DQ

Admission Free

Opening Hours: Wednesday-Sunday 12-5

www.heonggallery.com

Mel Bochner

Do I Have to Draw You a Picture, 2013

Etching with aquatint printed in blue on white wove paper, 56.5 × 77 cm.

© Mel Bochner. Collection: The British Museum.

Kay Rosen

She-Man, 1996 – 2018

Sign paint on wall, dimensions variable.

© Kay Rosen. Courtesy the artist and Philipp Pflug Contemporary.